Negative Plantar (or palmar) Angle in Horses: Why It Matters and How to Spot It

Negative Plantar Angle (NPA) is one of those topics that, once you understand it, you’ll start seeing everywhere. It’s a common yet often-overlooked hoof imbalance that can have widespread consequences for a horse’s movement, comfort, and long-term soundness.

It’s also one of my personal “soapbox” issues — because when we miss it, we miss a huge piece of the puzzle in so many “mystery” hind-end lameness cases. Over the past month alone, I’ve seen it crop up repeatedly in client horses, which is usually the universe’s way of telling me, “Okay, it’s time to write about this again.”

So let’s break it down. By the end of this article, you’ll know:

What NPA is and how it differs from a normal hoof angle

Why it matters biomechanically

How it affects both front and hind limbs

How to recognize it (even without radiographs)

The potential long-term consequences if left unaddressed

Steps to prevent and address it

What Is Negative Plantar/Palmar Angle?

The “plantar” angle refers to the angle of the coffin bone (P3) in the hind foot relative to the ground. In the front feet, we call it the “palmar” angle — but the concept is the same.

In a healthy, balanced hoof, this angle is positive, meaning the tip of the coffin bone points slightly downward toward the ground. A normal positive plantar or palmar angle is generally 3–8 degrees, depending on the horse’s natural conformation.

When the angle drops below 3 degrees, we start to consider it “functionally negative” — meaning that even if it’s not technically pointing upward yet, it’s close enough to cause mechanical problems.

In more severe cases, the coffin bone actually tips upward at the toe — creating a truly negative angle.

Visualize it like this:

Positive angle – tip of the coffin bone pointing slightly down

Zero angle – coffin bone parallel to the ground

Negative angle – tip of the coffin bone pointing up

Positive Angle

Ground Parallel - zero degrees

Negative Angle

Why Negative Plantar Angle Matters

A horse’s hoof isn’t just the end of the leg — it’s the foundation for the entire musculoskeletal system. When the coffin bone is out of balance, it changes how every joint and soft tissue structure above it functions.

With NPA, the altered coffin bone position forces the pastern, fetlock, hock, stifle, pelvis, and even the back into a compensatory posture. That compensation creates chronic abnormal strain on muscles, tendons, ligaments, and joints.

Specific biomechanical consequences include:

Increased strain on the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) – due to its altered angle of attachment to the coffin bone

Increased tension on the suspensory ligament – especially in hind feet, predisposing to suspensory injury

Change in resting joint angles – altering load distribution through the hock, stifle, and sacroiliac joints

Shift in center of mass – often placing more load on the forehand and reducing hind limb engagement

Hind Feet: The Hidden Trouble Spot

Negative plantar angle in the hind feet is particularly problematic because it often hides behind vague symptoms:

“Mystery” hind end lameness

Poor engagement or impulsion

Difficulty with collection or transitions

Reluctance to back up or step under

Hock and stifle soreness

Sacroiliac (SI) discomfort

Low-grade or recurring suspensory injuries

Many of these horses have been through rounds of diagnostics, injections, and training changes with only partial improvement — because the hoof mechanics are still forcing the same faulty loading patterns.

Front Feet: Navicular-Type Symptoms

In the front limbs, a negative palmar angle can mimic or contribute to “navicular” pain. The increased strain on the DDFT, navicular bone, and surrounding structures can cause:

Short, choppy strides

Toe-first landing

Intermittent lameness

example of an NPA front hoof, this mare was diagnosed with Navicular Syndrome

A Quick Way to Feel What NPA Does

If you want to understand how NPA affects the rest of the body, try this experiment:

Tape a pencil under the ball of your foot so your toe is slightly lifted.

Walk around for five minutes.

You’ll quickly notice strain in your calves, knees, hips, and lower back. That’s what your horse feels — except they’re carrying their body weight plus a rider’s, and they can’t untape the pencil at the end of the 5 minutes.

How to Recognize NPA Without X-Rays

While radiographs are the gold standard for measuring coffin bone angles, you can often spot NPA from external signs, or at least recognize when imaging is likely needed..

1. Bullnosing of the dorsal hoof wall

Instead of a straight line from coronet band to ground, the dorsal wall of an NPA hoof often appears convex (bulging outward).

Laminitis tends to create a concave/dished profile.

NPA tends to create a convex/bullnosed profile.

A healthy hoof should have a straight hoof wall.

Dished appearance of a laminitic hoof

Straight hoof wall - normal

“Bullnosed” convex appearance of an NPA hoof

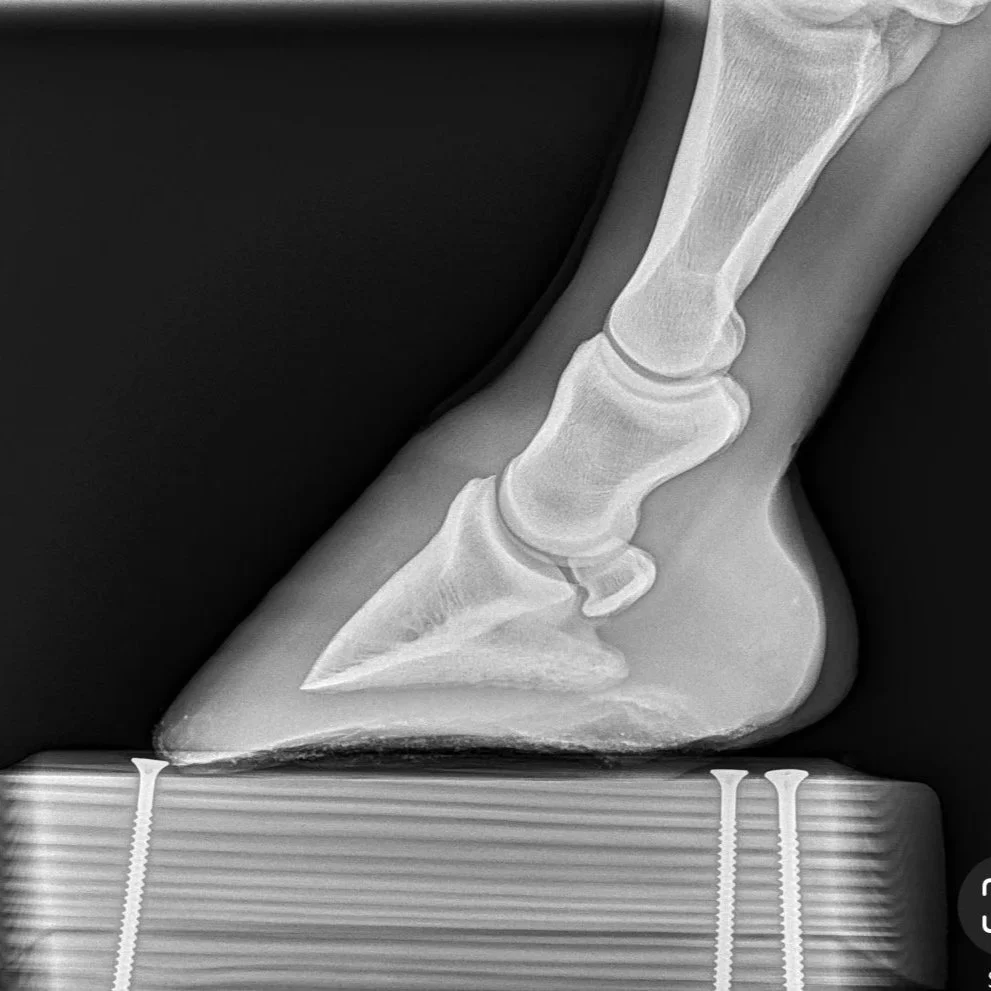

Right hind: Coffin bone is 2* NPA

Radiograph belonging to this RH

Left hind: Ground parallel coffin bone, 0* angle

Radiograph belonging to this LH

2. Coronary band angle “quick screen”

Stand to the side of the hind limb and mentally extend the line of the coronary band forward:

In a normal hind foot, that line will intersect somewhere on the forearm just above the carpus (knee).

In an NPA hind, the line will often hit the elbow — or even the belly.

This isn’t a diagnostic test, but it’s a useful quick screen.

See how Cheyenne’s line hits her in the elbow? She also has stifle arthritis, no surprise.

She is NPA behind with ground parallel coffin bones.

3. Digging toes into soft footing

NPA horses often paw or “dig in” when standing in sand or deep bedding. They’re instinctively trying to wedge their toes down to recreate a more normal coffin bone position.

This horse is digging his RH toes into the arena footing to find a more comfortable alignment

This mare digs her hind toes into the sand for comfort

This is a radiograph of her right hind, which is NPA

What Causes NPA?

NPA develops when the hoof capsule grows or wears in a way that allows the heels to collapse under the limb, bringing the back of the coffin bone lower relative to the toe.

Contributing factors include:

Poor hoof trimming/shoeing balance – heels left too long and forward, underrun heels not addressed

Long-term hoof neglect – overgrowth changing the capsule’s orientation

Injury or conformation issues higher up – causing chronic uneven loading

Long term shoeing in metal shoes - causing failure of the caudal hoof structures (digital cushion atrophies, frog prolapses)

Why NPA Is Self-Perpetuating

Once the hoof capsule distorts into an NPA, the altered mechanics create more heel collapse — which worsens the angle. The longer it persists, the more secondary problems arise higher up the limb, making the rehab more complex.

The Bigger Picture: Compensations Throughout the Body

Because hoof balance influences every joint above it, NPA horses often present with a domino effect of issues:

Tight hamstrings from working in a constant “pushed back” stance

Lumbar and SI joint restriction from altered pelvic tilt

Kissing spines

Shoulder girdle soreness and collapsed thoracic sling from increased forehand loading

Stifle issues - locking stifles, arthritis, meniscal or ligament tears

And here’s the kicker: these compensations don’t always disappear the moment the hoof is corrected. The horse may need time — and supportive therapy — to relearn normal movement patterns.

Addressing and Preventing NPA

1. Corrective trimming/shoeing

Heels should be trimmed back to the widest part of the frog, not left running forward.

Quarter arches must be maintained to help bring the heels back.

If there is excessive toe height shown on radiographs, it should be removed. Exercise caution! Sometimes the coffin bone is not where you think. There is not always adequate sole depth to remove additional toe height safely!

The goal is to restore a positive plantar/palmar angle over time, not force an instant fix.

In some cases, wedges or supportive pads are used temporarily to reduce strain while the hoof grows into better balance.

2. Supportive farriery

Wedge pads and frog support with boots or composite shoes may help realign the coffin bone while protecting soft tissues during the transition.

This should always be combined with a plan for gradual capsule reshaping, not just used as a permanent crutch.

3. Whole-horse rehab

Address muscle tightness and joint restriction caused by long-term compensation.

Incorporate in-hand work, hill work, and proprioceptive exercises to restore normal spinal mobility and limb use.

4. Pain management

Horses with significant soft tissue strain may need veterinary support or ongoing manual therapy support (bodywork, massage, physiotherapy) to stay comfortable during rehab.

5. Regular monitoring

Frequent trims (every 3-4 is ideal, 6 weeks max) to prevent heels from running forward again.

Radiographs to track angle changes, especially in severe cases.

Case Study: “Mystery” Hind End Lameness

A 12-year-old Warmblood gelding presented with intermittent hind-end lameness, worse on circles. He had been treated with hock injections twice in two years with only mild improvement.

On evaluation, his hind feet showed pronounced bullnosing and a coronary band angle intersecting at the elbow. Radiographs confirmed a -2° plantar angle in both hinds.

With corrective trimming every 4 weeks, gradual heel support, and a tailored exercise plan, his plantar angles returned to +4° over 8 months. His “hock lameness” resolved without further injections.

The Takeaway

Negative plantar or palmar angle isn’t just a hoof issue — it’s a whole-horse issue.

It changes joint angles, strains tendons and ligaments, and can mimic or contribute to lameness higher up the limb.

The good news? It’s relatively easy to spot once you know what to look for, and with the right combination of hoof care, bodywork, and exercise, most horses can return to comfortable, functional movement.

The bottom line:

A few degrees at the hoof can mean a world of difference for the horse above it.